Sample Required: Stool | Test Type: Immunity

Key Advantages

The ability to digest and selectively absorb nutrients from our foods and beverages is one of the cornerstones of good health. To obtain benefits from food that is consumed, nutrients must be appropriately digested and then efficiently absorbed into portal circulation. Microbes, larger sized particles of fibre, and undigested foodstuffs should remain within the intestinal lumen. Poor digestion and malabsorption of vital nutrients can contribute to problems with degenerative diseases, compromised immune status, and deficiency states caused by inadequate mineral, vitamin, carbohydrate, fats, and amino acids status.

In addition to digestion and selective absorption, the gastrointestinal tract eliminates undigested food residues and toxins that are excreted via the bile into the intestinal tract and provides a niche for the proliferation of friendly microorganisms.

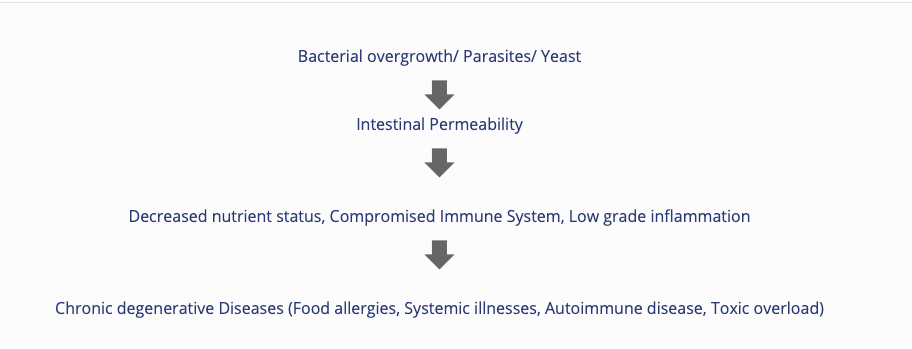

Impairment of the selective absorptive capacity or of the barrier function of gut (as in “excessive intestinal permeability”) can result from a number of suspected causes. Common associated causes include: low stomach acid; chronic maldigestion; food allergens’ impacting on the bowel absorptive surfaces; bacterial overgrowth or imbalances (dysbiosis); pathogenic bacteria, yeast or parasites with related toxic irritants; and the use of NSAID’s and antibiotics.

Impairment in intestinal function can contribute to the development of food allergies, systemic illnesses, autoimmune disease, and toxic overload from substances which are usually kept in the confines of the bowel for elimination.

Gastrointestinal (GI) complaints are among the most common reasons that patients seek medical care.

A state where the beneficial host bacteria is compromised by an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria. Pathogens can interfere with certain metabolic pathways and cause a knock on effect on other organ systems in the body. It is particularly beneficial to identify these pathogens to tailor a treatment plan accordingly and far more specifically.

Bacteria:

Role of Beneficial Bacteria:

Yeasts:

Infection with yeast species can cause a variety of symptoms, both intra- and extra- gastrointestinal, and may escape suspicion as a pathogenic agent in many cases. Controversy remains as to the relationship between Candida infection and episodes of recurrent diarrhoea.1 However, episodes of yeast infection after short-term and long-term antibiotic use has been identified in patients with both gastrointestinal and vaginal symptoms.2 Identification of abnormal levels of specific yeast species in the stool is an important diagnostic step in therapeutic planning for the patient with chronic gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal symptoms.

Parasites:

It is very important, and most cost effective, that 3 specimens are collected on 3 separate days. Parasites do not shed and their eggs do not appear on stool specimens on a homogenous/regular basis. One day’s sample may produce negative results, while the following day’s sample may be positive.

This analysis of the stool specimen provides fundamental information about the overall gastrointestinal health of the patient. When abnormal microflora or significant aberrations in intestinal health markers are detected, specific interpretive paragraphs are presented.

If no significant abnormalities are found, interpretive paragraphs are not presented.

Beneficial flora include lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, clostridia, Bacteroides fragilis group, enterococci, and some strains of Escherichia coli. The beneficial flora have many health-protecting effects in the gut, and as a consequence, are crucial to the health of the whole organism. Some of the roles of the beneficial flora include digestion of proteins and carbohydrates, manufacture of vitamins and essential fatty acids, increase in the number of immune system cells, break down of bacterial toxins and the conversion of flavinoids into anti-tumour and anti-inflammatory factors.

Lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, clostridia, and enterococci secrete lactic acid as well as other acids including acetate, propionate, butyrate, and valerate. This secretion causes a subsequent decrease in intestinal pH, which is crucial in preventing an enteric proliferation of microbial pathogens, including bacteria and yeast. Many GI pathogens thrive in alkaline environments. Lactobacilli also secrete the anti fungal and antimicrobial agents lactocidin, lactobacillin, acidolin, and hydrogen peroxide. The beneficial flora of the GI have thus been found useful in the inhibition of microbial pathogens, prevention and treatment of antibiotic associated diarrhoea, prevention of traveler’s diarrhoea, enhancement of immune function, and inhibition of the proliferation of yeast.

In a healthy balanced state of intestinal flora, the beneficial flora make up a significant proportion of the total microflora. Healthy levels of each of the beneficial bacteria are indicated by either a 3+ or 4+ (0 to 4 scale). However, some individuals have low levels of beneficial bacteria and an overgrowth of nonbeneficial (imbalances) or even pathogenic microorganisms (dysbiosis). Often attributed to the use of antibiotics, individuals with low beneficial bacteria may present with chronic symptoms such as irregular transit time, irritable bowel syndrome, bloating, gas, chronic fatigue, headaches, autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), and sensitivities to a variety of foods.

Treatment may include the use of probiotic supplements containing various strains of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria and enterococci and consumption of cultured or fermented foods including yogurt, kefir, miso, tempeh and tamari sauce.

The Comprehensive Stool Analysis with Parasitology x 3 identifies live bacteria and yeast, parasites, maldigestion, bacterial metabolism, inflammation and immune function. Important information regarding the efficiency of digestion and absorption can be gleaned from the measurement of the faecal levels of elastase (pancreatic exocrine sufficiency), muscle and vegetable fibers, carbohydrates, and total fat.

Inflammation can significantly increase intestinal permeability and compromise assimilation of nutrients. The extent of inflammation, whether caused by pathogens or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), can be assessed and monitored by examination of the levels of biomarkers such as lysozyme, lactoferrin, white blood cells and mucus.

These markers can be used to differentiate between inflammation associated with potentially life threatening inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which requires life long treatment, and less severe inflammation that can be associated with the presence of entero-invasive pathogens. Lactoferrin is only markedly elevated prior to and during the active phases of IBD, but not with IBS. Monitoring faecal lactoferrin levels in patients with IBD can therefore facilitate timely treatment of IBD, and the test can be ordered separately.

sIgA is the only bona fide marker of humoral immune status in the GI tract and represents the first line of defence of the GI mucosa by acting as the immune barrier. Since the vast majority of secretory IgA (sIgA) is normally present in the GI tract where it prevents binding of pathogens and antigens to the mucosal membrane, it is essential to know the status of sIgA in the gut. Elevated faecal sIgA levels generally indicate a response to antigenic presence.

Short Chain Fatty Acids are the end product of the bacterial fermentation process of dietary fibre.

The SCFA markers tested in the CSA give an indication of the individuals’ fibre intake as well as any potential dysbiosis that together determines the health of the intestinal tract. SCFAs decrease the pH of the intestines and therefore make the environment unsuitable for pathogens, including bacteria and yeast.

To ensure optimal levels, adequate fibre should be an important part of the diet. Sources of soluble fibre include fruits, vegetables, oat bran, barley, seed husks, flaxseed, psyllium, dried beans, lentils, peas. Sources of insoluble fibre include wheat bran, corn bran, rice bran, the skins of fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, dried beans and wholegrain foods; resistant starch include unprocessed cereals and grains, firm bananas, potatoes and lentils.

The role of SCFA’s includes their role as nutrients for the colonic epithelium, as modulators of colonic and intracellular pH, cell volume and other functions associated with ion transport, and as regulators or proliferation, differentiation and gene expression (Cook and Sellin, 1998).

Normal healthy stool should be brown and soft but formed in consistency. Food and water consumption causes variations to the colour and consistency of the stool on a day-to-day basis. It is affected by pigments in foods, dietary supplements, bile, fibre, water and intestinal transit time. Keeping a check on the appearance of stool is an important way of ensuring the gastrointestinal tract is as healthy as possible to avoid chronic conditions developing.

Impairment of intestinal functions can contribute to the development of food allergies, systemic illnesses, autoimmune disease, and toxic overload from substances that are usually kept in the confines of the bowel for elimination. Efficient remediation of GI dysfunctions incorporates a comprehensive guided approach that should include consideration of elimination of pathogens and exposure to irritants, supplementation of hydrochloric acid, pancreatic enzymes and pre- and probiotics, and repair of the mucosal barrier.

Certain dysbiotic bacteria may appear under the Commensal category if found at low levels because they are not likely pathogenic at the levels detected. These are more a sign of imbalances in other populations or elsewhere in the digestive tract. When imbalanced flora appear, it is not uncommon to find inadequate levels of one or more of the beneficial bacteria and/or a faecal pH which is more towards the alkaline end of the reference range (6.5 – 7.2). It is also not uncommon to find hemolytic or mucoid E. coli with a concomitant deficiency of beneficial E. coli and alkaline pH, secondary to a mutation of beneficial E. coli in alkaline conditions (DDI observations). Treatment with antimicrobial agents is unnecessary unless bacteria appear under the dysbiotic category. Addressing Concomitant imbalances remains the priority.

Intestinal parasites are abnormal inhabitants of the GI tract that live off and have the potential to cause damage to their host. Factors such as contaminated food and water supplies, day care centers, increased international travel, pets, carriers such as mosquitoes and fleas, and sexual transmission have contributed to an increased prevalence of intestinal parasites.

Parasites often have complex life cycles and routes of transmission. During this process parasites can be found as either TROPHS (active organisms) or CYSTS (dormant eggs or ‘ova’).

Note: Most parasites are acquired in their cyst state (before decystation within the body).

In general, acute manifestations of parasitic infection may involve diarrhoea with or without mucus and/or blood, fever, nausea, or abdominal pain. However, these symptoms do not always occur. Consequently, parasitic infections may not be diagnosed and eradicated. If left untreated, chronic parasitic infections can cause damage to the intestinal lining and can be an unsuspected cause of illness and fatigue. Chronic parasitic infections can also be associated with increased intestinal permeability, irritable bowel syndrome, irregular bowel movements, malabsorption, gastritis or indigestion, skin disorders, joint pain, allergic reactions, decreased immune function, and fatigue.

* Consult latest medical eradication protocols for all specific parasites detected.

Blastocystis hominis

Blastocystis hominis is a common protozoan found throughout the world. Blastocystis is transmitted via the faecal- oral route or from contaminated food or water.

Whether Blastocystis infection can cause symptoms is still considered controversial. Symptoms may be compounded by concomitant infection with other parasitic organisms, bacteria, or viruses. Often, B. hominis is found along with other such organisms. Nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, anal itching, weight loss, and excess gas have been reported in some persons with Blastocystis infection.

Medically recommended therapy can also eliminate G. lamblia, E. histolytica and D. fragilis, all of which may be concomitant undetected pathogens and part of patient symptomatology. Various herbs may also be effective. It is advisable to limit refined carbohydrates in diet.

Giardia

Giardiasis is a diarrhoeal illness caused by the parasite Giardia intestinalis (also known as Giardia lambli). Giardia lamblia is flagellated protozoan that infects the small intestine and is passed in stool and spread by the faecal-oral route. Waterborne transmission is the major source of giardiasis.

Giardiasis is one of the most common parasitic infections in the western world, infecting nearly 2% of adults and 6% to 8% of children.

People become infected with Giardia by swallowing Giardia cysts found in contaminated food or water. Cysts are instantly infectious once they leave the host through faeces. An infected person might shed 1-10 billion cysts daily in their faeces and this might last for several months. However, swallowing as few as 10 cysts might cause someone to become ill. Giardia may be passed person-to-person or even animal-to-person. Also, oral-anal contact during sex has been known to cause infection. Symptoms of Giardiasis normally begin 1 to 3 weeks after a person has been infected.

Water filtration/sanitation is the primary method for reducing Giardia infection in the home, as well as maintaining good faecal hygiene practices around pets and bathroom.

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidiosis is a diarrhoeal disease caused by an intestinal infection of Cryptosporidium parvum, a microscopic parasite. Cryptosporidiosis occurs worldwide and appears to be a relatively common cause of acute diarrhoea in young children, especially during warmer months of the year.

Cryptosporidium can spread from direct person-person contact or waterborne transmission. As well as infecting humans, Cryptosporidium parvum occurs in a variety of animals including dogs and cats. The infection is usually not serious in those with competent immune systems. However in situations of weakened immunity (e.g. cancer treatment, steroid therapy and HIV/AIDS) severe and long lasting illness may develop, and can be fatal.

The most common symptom is diarrhoea, which is usually watery and may be profuse. Other symptoms that may occur are nausea, vomiting, fever, headache and loss of appetite. However some infected with Cryptosporidium may appear asymptomatic.

The microscopic finding of yeast in the stool is helpful in identifying whether the proliferation of fungi, such as Candida albicans, is present. Yeast is normally found in very small amounts in a healthy intestinal tract. While small quantities of yeast (reported as none or rare) may be normal, yeast observed in higher amounts (few, moderate to many) is considered abnormal.

An overgrowth of intestinal yeast is prohibited by beneficial flora, intestinal immune defense (secretory IgA), and intestinal pH. Beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus colonise in the intestines and create an environment unsuitable for yeast by producing acids, such as lactic acid, which lowers intestinal pH. Also, lactobacillus is capable of releasing antagonistic substances such as hydrogen peroxide, lactocidin, lactobacillin, and acidolin.

Many factors can lead to an overgrowth of yeast including frequent use of antibiotics (leading to insufficient beneficial bacteria), synthetic corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, and diets high in sugar. Although there is a wide range of symptoms which can result from intestinal yeast overgrowth, some of the most common include brain fog, fatigue, recurring vaginal or bladder infections, sensitivity to smells (perfumes, chemicals, environment), mood swings/depression, sugar and carbohydrate cravings, gas/bloating, and constipation or loose stools.

A positive yeast culture (mycology) and sensitivity to prescriptive and natural agents is helpful in determining which anti-fungal agents to use as part of a therapeutic treatment plan for chronic colonic yeast. However, yeast are colonizers and do not appear to be dispersed uniformly throughout the stool. Yeast may therefore be observed microscopically, but not grow out on culture even when collected from the same bowel movement.