Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and globally. During menopause when estrogen levels drop, a woman’s risk of cardiovascular disease increases. This is because estrogen provides a protective effect against heart disease in women. In fact, estrogen has been shown to decrease blood pressure, improve cholesterol, and protect against atherosclerosis.

If estrogen plays an important role in supporting cardiovascular health in women, why isn’t menopausal hormone replacement therapy (MHRT) an option for all women? It turns out that some studies have shown that MHRT can increase cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This increased risk, however, is likely influenced by the formulation and route of administration of the MHRT prescribed, a woman’s health history, and age at which MHRT is initiated.

MENOPAUSAL HORMONE CHANGES ARE ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE RISK

Estrogen provides a protective effect against heart disease in women. It lowers blood pressure by increasing blood flow and dilating small arteries, improves cholesterol by lowering LDL and increasing HDL, protects against atherosclerosis, and even helps prevent low vitamin D levels and osteoporosis, two factors that are associated with an increase in cardiac events. It’s no wonder then, that during menopause when estrogen levels drop, a woman’s risk of cardiovascular disease increases. Remember that menopause is the cessation of ovarian hormone cycles and fertility in women that occurs anywhere from age 40-58, with the average age being 51.

WHAT IS MENOPAUSAL HRT?

Menopausal HRT is a collection of prescription hormone receptor agonists (synthetic or bioidentical hormones) used in menopause to reduce or eliminate symptoms of menopause. It generally refers to the prescription of estrogens and progestogens , although other hormones are sometimes used in post-menopausal women.

MHRT is not currently approved for the prevention or treatment of cardiovascular disease, but it is approved for the following:

- Moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS)

- Moderate to severe vulvovaginal symptoms: vaginal atrophy (VVA) and dyspareunia

- Prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women

- Hypoestrogenism from hypogonadism, surgical menopause (bilateral oophorectomy), or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI)

It is important to note that there are many forms of estrogens available: conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs), synthetic conjugated estrogens, esterified estrogens, synthetic ethinyl estradiol, and bioidentical estradiol (17β-estradiol; often simply referred to as E2).

Likewise, there are many forms of progestogens available. Progestogen is an umbrella term that includes synthetic and bioidentical forms. Progestins are synthetic progestogens. Progesterone is a bioidentical progestogen. Progestogens are combined with estrogens in women with a uterus to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia that occurs with estrogen.

There are various contraindications to MHRT. The cardiovascular-related contraindications include history of:

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), as seen with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Stroke

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Coronary heart disease (CHD)

- Blood clotting disorders

It is interesting to note that there is some evidence that stroke, heart attack, and clotting risk is improved with estrogen therapy depending on the formulation, route of administration, and health of the patient.

THE WOMEN’S HEALTH INITIATIVE

The most prominent study on HRT is the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). It was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) looking at women aged 50-79 . This study used only oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs) and oral synthetic progestin, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). CEEs alone were used in women without a uterus and CEEs + MPA in women with a uterus . The study DID NOT use bioidentical estradiol (E2) or bioidentical progesterone.

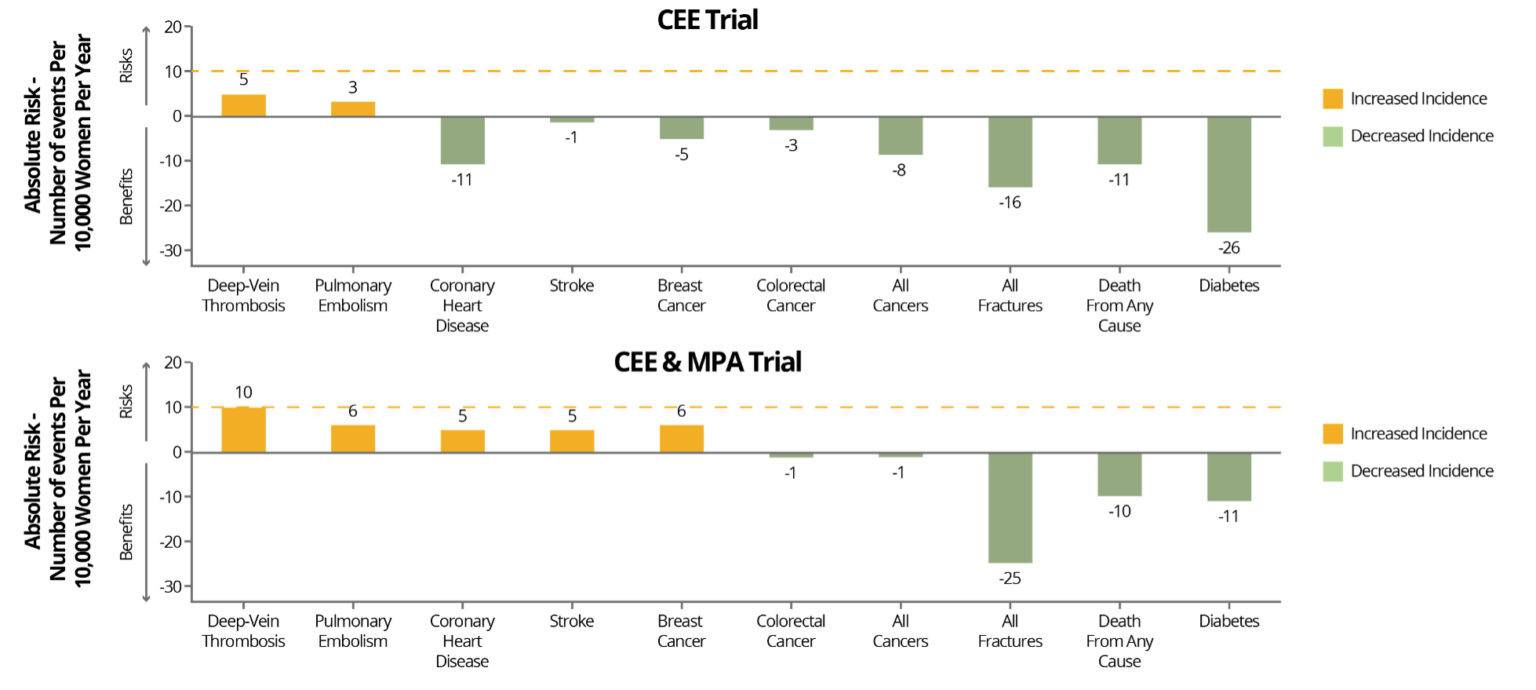

The initial interpretation of the WHI hurt the public perception of MHRT, as initial negative results were heavily publicized. However, subsequent careful analysis demonstrated the WHI had many positive findings, especially for women aged 50-59 (the most common type of MHRT patient), and all cardiovascular risks were considered rare. For example, when combining the data from both oral CEE + MPA (average use 5.6 years) and oral CEE alone (average 7.2 years) groups after a median of 18 years follow-up, the WHI outcomes for women aged 50-59 found no increased CVD mortality, reduced coronary heart disease (CHD), and a reduction in all-cause mortality!

Women aged 50-59 taking oral CEE had an increased incidence of VTE, however, and women taking oral CEE + MPA additionally had an increased incidence coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke. As stated earlier, although these risks were identified, the risk increases remained “rare” at <10/10,000 women per year. Despite these incidents remaining in the “rare” category, subjects taking oral MPA, the synthetic progestin, had double the risk of VTE and significantly greater CVD risk than those who did not take MPA. Subsequently, oral MPA has been linked to increased thrombogenesis (increased clotting factors) where oral bioidentical progesterone has not.

It is now over 20 years since the WHI, and continued follow-up and data analysis found that the MHRT used in the study has more health benefits than risks when initiating in women aged 50-59 or within 10 years of menopause. Combining the data from the WHI and other studies, it has been found that the oral route for estrogens and synthetic progestins are thrombogenic, and age as well as baseline health should be considered. Therefore, most major associations conclude that the rare risks identified may be mitigated by appropriate CVD screening and using safer formulations and routes of administration (e.g., transdermal E2 instead of oral CEE and bioidentical progesterone instead of MPA, which will be discussed next).

GRAPH:

NAMS. Menopause. 2022;29(7):767-794.

Share:

Related Posts

Benefits of Creatine in Perimenopause and Menopause

Written by Maura MacDonald, MS, RD, CSSD | 2025 As we age, the notion is that we will inevitably become weaker. Not as mobile as

Goodbye Pie Chart, Hello Phase 1 Sliders

Written by Allison Smith, ND | 2025 As we usher in a new era of DUTCH testing which leaves behind the concept of the three-way

Introducing the DUTCH Dozen

Written by Kelly Ruef, ND | 2025 Hormone testing can be complex, which is why Precision Analytical developed the DUTCH Dozen, an interpretive framework that

DUTCH Report Enhancements

Written by Hilary Miller, ND | 2025 Precision Analytical have released the newest version of the DUTCH Test. This is the report’s most significant update

Gallbladder Health 101: What It Does and How to Keep It Working Well

Written by Ashley Palmer & Pooja Mahtani | 2025 The gallbladder may not get much attention compared to the gut, but it plays a central